Shelf Life I

First We Take Manhattan: An Afternoon at Strand Books | HJL Books #5

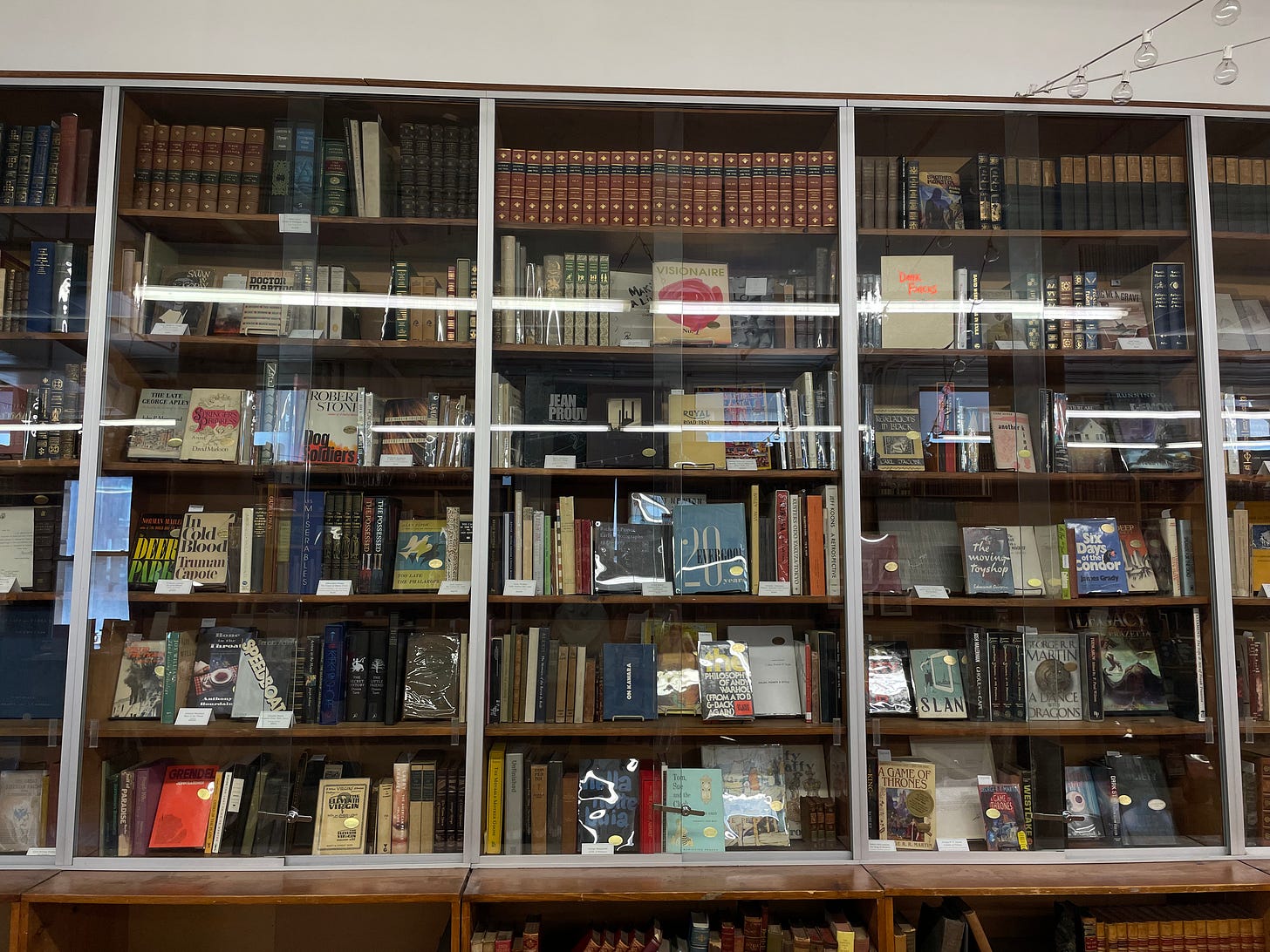

It was a shaded August afternoon in Manhattan—the light was slow and the late-summer air pressed down heavily. In the midst of my dash from one New York City airport to another, I had managed to make time for a brief stop at The Strand, the storied Union Square bookshop. Although The Strand boasts tens of miles of shelves, I had headed straight for the few yards of present interest, being the glass cabinets in the Rare Book Room on the top floor.

“Have you read that?”

I gestured toward the slim volume a man beside me had just pulled down and balanced against his hip. He looked to be in his mid-fifties, with a round, youthful face framed by a new baseball cap and dark, thick-rimmed glasses. He wore midnight-blue jeans, an oversized sport jacket, and carried himself with a casual ease that indicated either inexperience, indifference, or a long familiarity with the books on the shelves before us.

When you stand before enough shelves, you learn to relax—outwardly, at least—in their presence. The stillness of this composure resembles the first moments of coming face to face with a collection of rare books, when someone either does not know what to do or simply remains unmoved. And so, someone who appears almost disinterested in the presence of books is either not looking at all or looking even more seriously than anyone else in the room.1

He glanced down at the book, raised it in front of his waist, and seemed to admire it privately for a moment before turning slightly towards me.

“It’s great.”

“Yes, great.”

“But the price isn’t great.”

“No.”

“But it’s alright.”

“Yes.”

His replies emerged cautiously through a stern, scratchy French accent, yet as our conversation went on, his initial reserve gave way to a gentle eagerness, his delight in the book overcoming what I took to be a customary hesitation to engage. Such is one of the many powers of books: no one has ever read something they have liked without wanting someone else to read it, enjoy it, and speak of it in turn.

“The author is virtually unknown in France.”

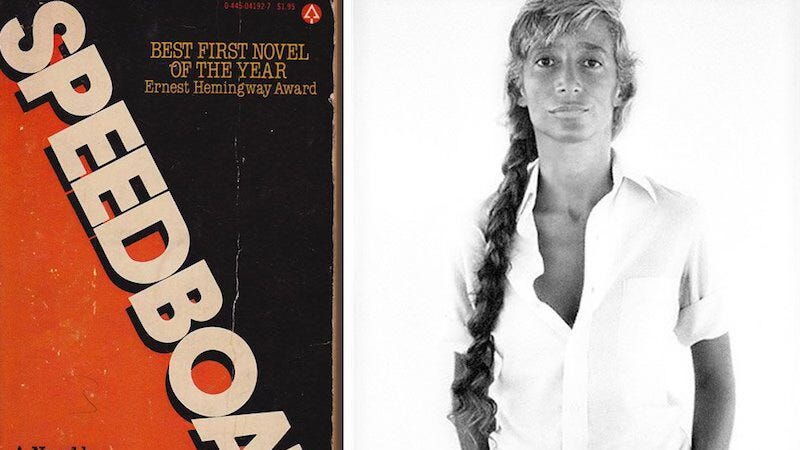

I would not have expected Renata Adler to have found much popularity in France, and I suspected she preferred it that way. The book was a first American edition of Speedboat (Random House, 1976), Adler’s debut novel. Its cover is split diagonally into two triangles, one silver and one black, bisected by bold white lettering set above a faint shadow. It was reissued by NYRB Classics in 2013.

Adler was born in Milan in 1937 to German Jewish parents who were in the midst of a six-year emigration journey from Nazi Germany, where they left in 1933, to the United States, where they arrived in 1939. She became a staff writer at the New Yorker in 1962, after completing an M.A. at Harvard, and continued writing throughout her life as a critic, novelist, and journalist, with spells as a law student and a professor of film and literature.

In Speedboat, Adler’s semi-autobiographical narrator, a young journalist named Jen Fain, recounts a passage from The Inferno, which she frames as a parable about reporting. Dante and Virgil come upon a man buried to his neck in boiling mud, who refuses to speak to them. “He has his own problems. He does not want an interview.” How does Dante get him to talk? “Dante actually grasps him by the hair and gets his story.” Had a book been within reach, Dante’s hair-pulling might have been entirely unnecessary.

I later learned that my browsing companion was returning to France—Paris—the next day, and that he and his wife (whom I was now able to identify as the woman giving me the occasional glare from across the room—spouses always look at book dealers with great wariness) had just been in Canada. They had stayed in John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s former room at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel in Montreal, where the anti-war anthem Give Peace a Chance was recorded in 1969.

I don’t think I could form as solid a connection with someone so quickly as by standing beside them in a bookstore. It puts you in a definite relationship; you discover points of closeness and distance. I suppose that’s all we want—to know where people stand. I have often identified people by the books they have bought. Rather than address someone I recognized by name, I would instead say that I remembered them buying X. You are given names but you choose books. (And people often imagine the latter is more difficult to remember).

He took another book into his hands, this time a signed first edition by Isaac Bashevis Singer. It reminded me of a letter I had seen recently, written by Henry Miller to Singer in response to Singer’s apology to him for winning the Nobel Prize. Miller said that Singer deserved it.

“You should buy that.”

“Yes.”

I told him briefly what I did—more or less how I had ended up browsing books alongside him.

“You live now in London?”

“Yes.”

“Do you know where I can find a Nineteen Eighty-Four?”

I said that I didn’t. Of course, you can find most things anytime—there are a number of first editions on the market—but I understood that he meant a copy that made a kind of outsized sense to buy; one that others didn’t know about, or some other shrewd opportunity.

I asked him where I could find Journey to the End of the Night, either in the American (Little, Brown and Company, 1934) or British (Chatto and Windus, 1934) first edition.

He laughed and said he had five, of each.

(Damn).

I asked him if he knew Gabriel Chevallier’s Fear. It was not published in English until the twentieth century, but it actually predated Journey, and I considered it as good as Céline.

“You compare it to Céline?”

“Yes.”

“Hmm. Chevallier. I am surprised. Chevallier…” He repeated the author’s name slowly, as if testing the syllables for some flaw.

“I believe what he came to write later was much different.”

“Hmm. Well, I will look for it. As good as Céline you say…”

“What about Barbusse?”

“Ah. Yes, Céline took after Barbusse, absolutely.”

We went on, meandering among authors and titles, as if drifting between scenes of a daydream.

I drew his attention to a tan clamshell box tucked into the side of the leftmost cabinet, just above eye level. Inside sat a first edition of Jack London’s Call of the Wild (Macmillan, 1903), its jacket remarkably well preserved, especially considering its age. We let out exclamations in our respective languages and lingered for a moment over its beauty.

“What’s the price?” He turned around to look for the shop assistant.

“It’s here.” She came forward and indicated toward the information card resting perversely in front of the book.

“Hmm. No, the price.”

“Here is the card, sir.”

“Ah, not that price. The price.”

“Sir…”

“Apologies, I may be getting lost in language…” he trailed off.

I decided to involve myself as kindly and unobtrusively as possible. “He is looking for your best price, or at least a lower one. To negotiate.”

“Yes.” He nodded politely in her direction, and then mine.

“Oh, I see. Well, we do not do that,” she replied. “Or, at least the person who does is not here.”

“It’s probably worth it,” I said.

“Perhaps. But not today.”

Some minutes later, I was carefully removing a couple of books from my suitcase—finds from my recent trip to Canada that I had begun to tell him about.

“I just bought a Kafka collection, an important one. But The Trial is not for me.” A moment before, I had placed in his hands a first British edition, published by Victor Gollancz in 1937. I exchanged it for another.

“Orion Press, 1959?”

“Yes.”

It was the first American edition of Primo Levi’s If This Is a Man.

“Where did you get this?” he asked with some vexation.

“Canada.” I smiled.

“And what do you want for it?”

I told him what I thought I could sell it for, and then the price at which I would be willing to sell it to him. It was considerably less.

He said that was still too much. I pulled up the listings for the few other copies floating around online and showed him why I thought it wasn’t.

“I see. You are probably right.”

“Maybe. But it’s not a matter of being right.”

I said I had to get on my way. He nodded, and we shook hands. I asked him to send me a note, and to let me know whenever he was in London. He said he would.

I paid for my books: an early signed Christopher Hitchens essay collection, a memoir by R.V.C. Bodley in a scarce jacket, an uncommon account of the Congo in the 1920s, a cult novel about New York City firefighting inscribed to someone, and a 1944 literary magazine. I sold the first three not long after arriving back in London.

I never learned his name—only that he had bought Adler’s Speedboat and Singer’s Satan in Goray.

In all likelihood, I will neither see nor hear from him again.

“Well, you know, you can’t win them all. In fact, you can’t win any of them,” an unnamed bartender in Speedboat says. To that, I would add: you don’t lose any of them either.

Or than any person looking seriously could actually be.

You write so well. This is excellent Harris.