Shelf Life II

Return to New York: Scenes from 'The Night Before the Book Fair' | HJL Books #6

Thursday Evening, Midtown

It’s the night before the opening of the Empire State Rare Book and Print Fair, for the first time being held at Grand Central. More pertinently, it’s also a few days into the 80th session of UN General Assembly. One event has been granted rather more police attention than the other. The private lanes of neon-orange pylons, the ribbons of SUV escorts, the screech of whistles, the swing of probing flashlights, swarming traffic marshals—none of it is for us.

But it is for us to get around. The great thing about this fair is that it puts booksellers at the centre of the action, letting books cross the paths of people who might otherwise never notice them. A common complaint of mine about book fairs, especially in the UK, is that they are over-optimized for booksellers and give too little consideration to the attending (or not) public, who might care more about convenience of access and the character of the space than the availability of parking and the ease of loading and unloading. I leave out book collectors from this calculation by intention, for they will come regardless, no matter the location or venue.1

I often say there are far more people who don’t collect books than those who do, and the real purpose of a book fair should be to reach that broader, uninitiated group. Otherwise it becomes just another day in the trade. Even if that day is more convenient, more social, and more conducive to internal business than others, it still offers little in the way of exposure or growth.

As I hinted at, we often end up on the wrong side of this deal in the UK. To be sure, there are successful fairs with strong public attendance, most notably Firsts at the Saatchi Gallery in May, the ABA fair at Chelsea Town Hall in early November, and the York Book Fair in September. On the other hand, a certain London hotel conference space is favoured by the trade far, far more than by the public2, the Oxford Rare Book Fair takes place twenty minutes uphill outside of town, and, more generally, the fact that book fairs happen almost every weekend across the country remains a confoundingly well-kept secret.

So I commend Fine Book Fairs, headed by Eve and Ed Lemmon, for attempting something difficult. But tonight we were all getting a bitter taste of our own medicine. For, there was effectively a no-go ring around Grand Central, and even the streets that remained open were at a complete standstill. I was in an Uber, having picked up five smallish but still sizeable boxes of vintage photoplay novels from a friend on the Upper East Side. For the last fifteen minutes, my driver had been circling the streets of Midtown searching for a way through the NYPD armour, but progress had stalled. With some apprehension I offered to get out of the car (to then do what, I wasn’t sure), but he was graciously willing to give it a few more tries.

Eventually he pulled over at an intersection and motioned toward a policeman blocking the entrance to the street.

“Maybe go talk to him.”

“The cop?”

“Yeah. He might let us through.”

I stepped out of the car and shuffled up to the officer as innocuously as possible.

“Hey, there’s a book fair at Grand Central.” He regarded me with a quizzical look. I continued, “Loading is supposed to be happening now. I have a bunch of books. Do you think I could I get to Lexington and 43rd?”

He turned, scoping the empty street beyond him, then faced me again, taking in my story or at least my look of pleading concern. If it was an excuse, it was not one he would hear often.

“Yeah,” he said slowly. “You’re good.”

I muttered my thanks, gave the driver a thumbs up, and scurried back to the car.

As we pulled through his motioning, another vehicle tried to follow. The policeman put his hand out and stepped in front of it, flashing his light straight into the windshield.

The car screeched to a stop, the driver’s window rolling down to reveal a shaking fist.

“Hey! What the hell!?”

“Book fair.”

It was the first time I had ever heard that term used in such a way.

It was probably my imagination, but through the glare of the back window I saw the policeman tip his cap to the books and the desperate bookseller he had just allowed gracious passage.

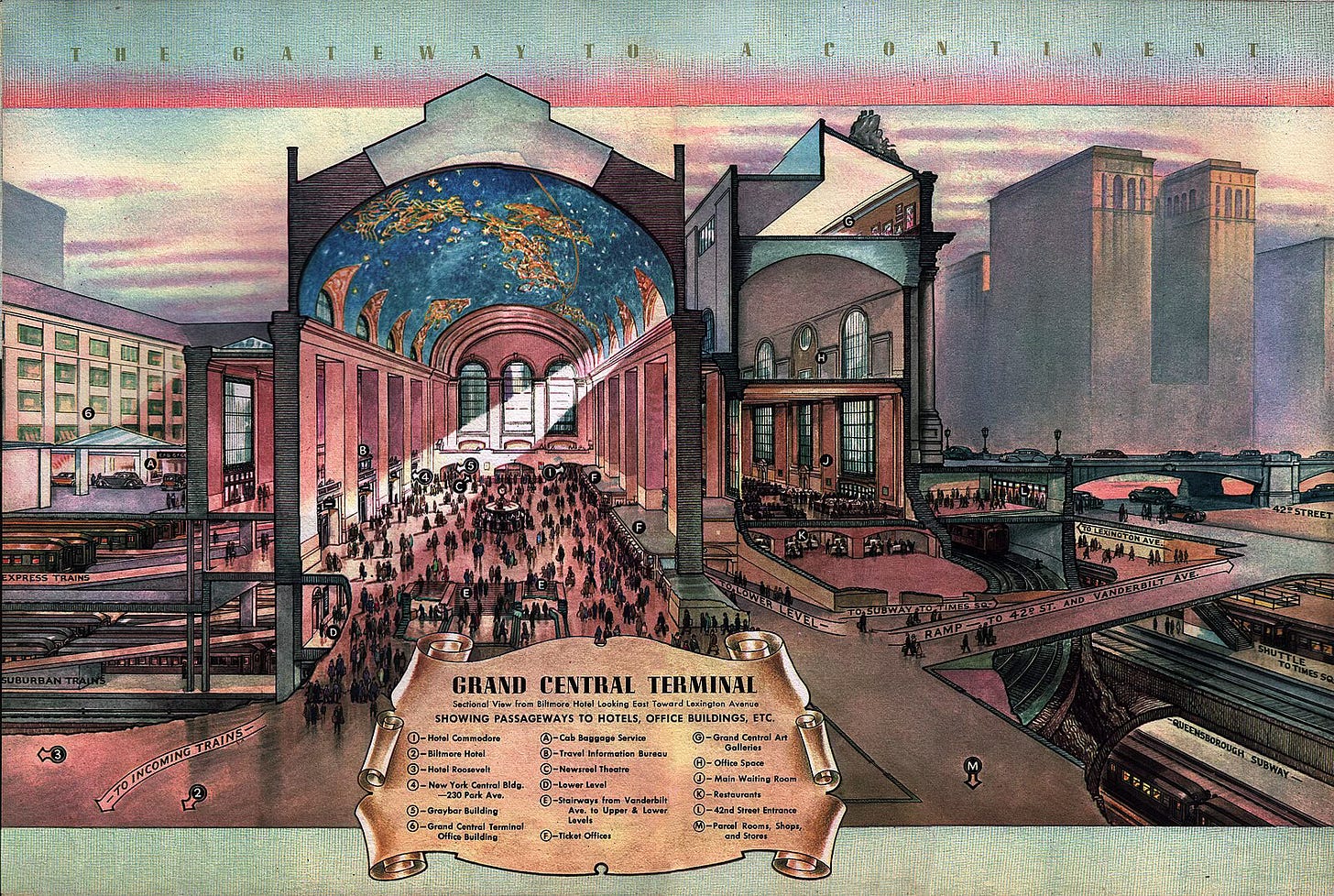

Thursday Evening, Grand Central

But there would be more gates, and more gatekeepers.

I sauntered into the station with the boxes stacked in a single column, supported by my hip and balanced against the right side of my head. If there is one skill a bookseller acquires above all others it is the art of carrying them, whether boxed, unboxed, in bags, or a mix of all three. With relief, I heard the unmistakable clutter of preparation and glimpsed a bustle of activity beyond a cordoned-off area. People were darting among boxes, tables, and glass cabinets like mice in a maze. I approached the line of stanchions and carefully eased my boxes to the ground.

At this point I should relate that Grand Central has its own police and fire departments. Seemingly, the chief objective of each organisation is to make you aware of that fact. The second is to be in charge of anything that goes on within the station. To this end, Grand Central even has its own emergency number. This means that if you call 911/999, and they ask you where you are, and you are within the boundary of Grand Central, they say you have called the wrong number and give you the number for Grand Central Emergencies instead. In all, despite forty-four platforms serving sixty-seven tracks, carrying three-quarters of a million passengers a day, thirty book and print dealers apparently had the potential to bring the entire system to its knees. One of the more urgent infractions concerned the ‘flammable’ nature of wooden bookshelves, which could only be quelled by marking them as if they were for sale3.

So it will not come as a surprise that the moment I had set down the boxes of books, a uniformed security guard came running toward me.

“Hey, you can’t be here.”

“Is this the book fair?”

“It is.”

“I’m dropping off some books.”

“No way. Look down—are you wearing hard-shell boots?”

“No.”

“Look up—are you wearing a hard hat?”

“No.”

“Have these even been sniffed”

“Sniffed?”

“The dogs.”

“The books?”

At this point, another man appeared, and though in plain clothes, redeemed by his hard hat and seemingly proper footwear. He and his colleagues were, as I now realised, the same figures I had moments earlier rather unkindly likened to mice. In fact, he was a porter, there to assist with the fair set-up.

“These your books?”

“Yeah.”

“They haven’t been checked,” the guard interrupted.

“Sniffed?” the porter replied.

“Yeah.”

The porter glanced over his shoulder, as if someone might be watching—or for a moment, wasn’t.

“Aight, fuck it.”

I was gone before the heavy could protest. I think neither heard my thanks, though I suppose I only one was meant to.

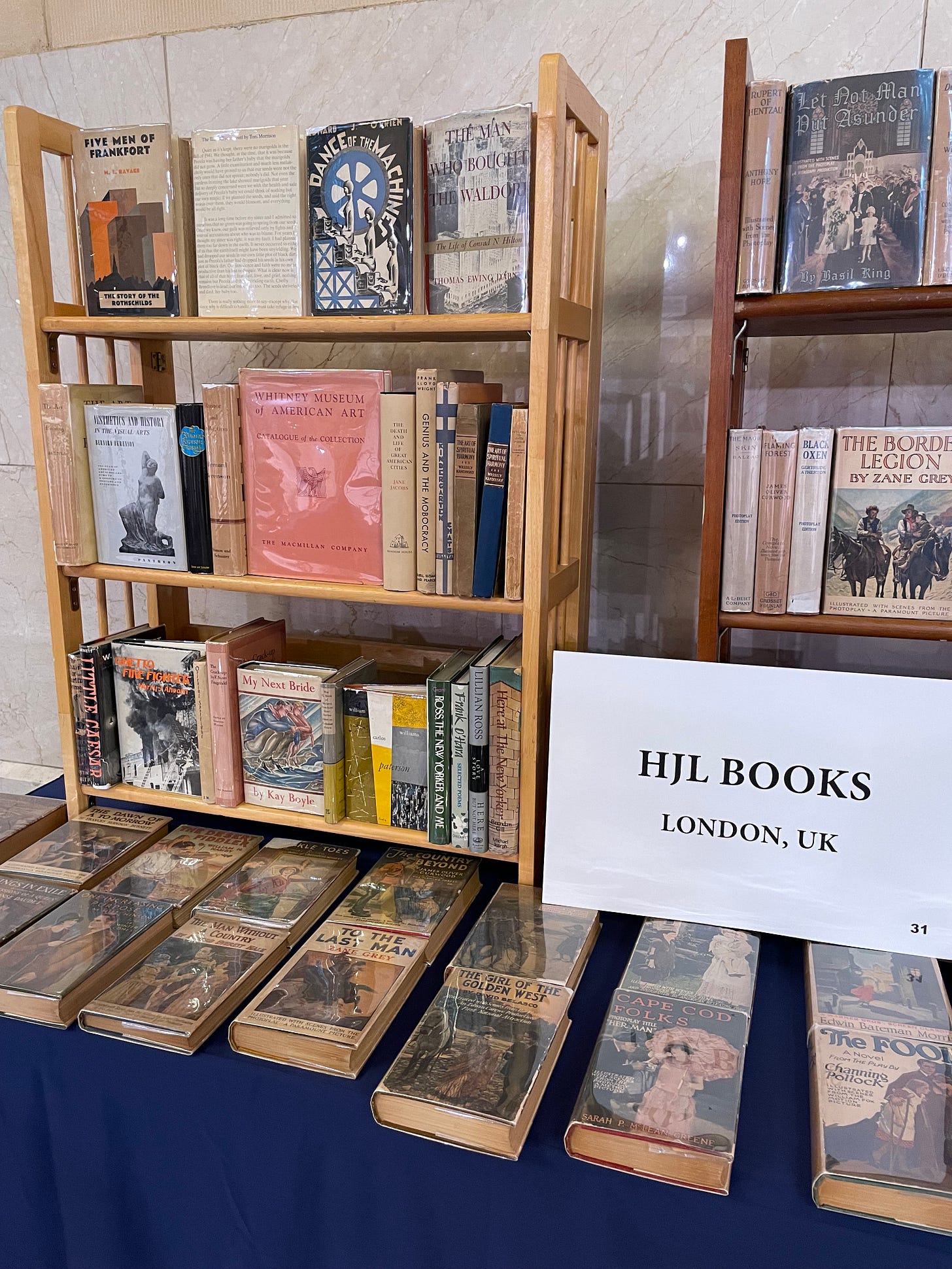

More on the fair itself to follow.

For now, I will only recount the line of the weekend:

“I don’t collect but I enjoy seeing everything that has not gotten destroyed.”

It was a thrill and an honour to be there.

There’s a great Nathan For You episode where Nathan Fielder tests how far, and through what obstacles, people will go to claim a ‘free’ TV. Through a convoluted price-match loophole with a Best Buy across the street, his store offers televisions for $1—but to reach them, customers must crawl through a narrow crawl-space that reveals a room that happens to be inhabited by a live alligator. The point is that some people try anyway. Book collectors are like this—God bless them.

To the extent that on a weekend in December, it may be the only place in London that people cannot be found.

They weren't.